23rd April has special resonance in England. It’s St George’s Day (England’s patron saint) as well as the traditional date on which to celebrate Shakespeare’s birth and death. Lesser known, however, is the fact that since 2010 it has also marked The United Nation’s English Language Day.

The U.N.’s Language Days seek to, ‘[…] entertain as well as inform, with the goal of increasing awareness and respect for the history, culture and achievements of each of the six working languages among the UN community.’ (United Nations)

As with the U.N.’s other working languages (Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French, and Russian), the history, culture, and achievements of English are impossible to summarise in a short blog; they are also not unproblematic. In many ways, English shares similarities with both St George and with Shakespeare. St George was born in Turkey in the 3rd century and many elements of the traditional St George narratives were added through the centuries. Much of Shakespeare’s life, similarly, is shrouded in mystery; what is clear however is that he had a good understanding of historical narratives, myths, and legends and he wove these through his work.

In English we similarly have great historical interweaving and addition. It is a giant amongst languages, both modern and historical. It is spoken at a ‘useful level’ by around 1.25 billion people- or around a quarter of the world’s population (some estimates are far higher than this). It is the language of Shakespeare and Mr Tumble, Martin Luther King and Beowulf. It is an official language for countries across the globe and a lingua franca (common language) enabling communication between millions of non-native English speakers every second. English is still the most widely used language on the internet, although there has been a growth in the use of other languages in recent years.

The History of English (Old English)

The story of how a collection of Germanic dialects spread from a tiny island in the North Atlantic to span the globe is an epic in its own right. The Open University has a very compressed (and amusing) history of the language but please see end sources for a longer read. Put briefly, modern day English is a great amalgam of different languages and dialects. At its root are the Anglo-Saxon dialects first brought to Britain in the 5th century AD. The Vikings brought Old Norse to the mix in the 9th century and many of England’s regional accents and dialects as well as place names have their origins in this linguistic hybridity. Old English and Old Norse are related languages, but certainly not identical. Until the Norman Invasion, the language is loosely called Old English.

Christianity brought Latin back to England in the 5th century, although it was primarily the lingua franca of the church. The Norman Invasion of 1066 established Norman French as the language of the elite and English, consequently, lost social status. Famously, the words for the living animal cared for by English-speaking underlings are in English (pig, sheep, cow), the words for the luxury meat are those of their French-speaking overlords (pork, mutton, beef).

For much of the history of English the country was not monolingual. In the streets of Viking Jorvik (York), for example, you were likely to hear Old English, Old Welsh, Middle Irish and even Arabic spoken as well as Norse. In medieval England most educated people would have been able to understand French and Latin as well as English, plus possibly another European language too.

The consequence of this mixed history is English’s extensive vocabulary with many words having multiple synonyms. Often the least formal word is Anglo-Saxon or Norse in origin and the most formal is often from French or Latin. Try the triples ‘fire/ flame/ conflagragration’ or ‘understanding/ comprehension/ sapience’, for example.

In the 14th century there was a resurgence of English during the period named Middle English. The 100 Years’ War had, perhaps, dulled the allure of French. The writer of the poem The Speculum Vitae (The Mirror of Life) writes in English rather than in French in the 14th century and tells us explicitly why:

Bot lered and lewed olde and Yonge Both educated and uneducated, old and young

Alle understonden englysch tonge (Vitae’) All understand English

This capacity for English to ease communication, along with its already hybrid nature, proved a great strength in the coming centuries. Already something of a melting pot English absorbed new words and constructions like a sponge. Where English encountered lexical gaps (lack of a word for something) it pilfered the languages of the world, magpie-like, to fill them. Thus we have words today that we have no idea are loan words or borrowings: Shampoo from Hindi, pyjama from Urdu, alcohol from Arabic and ketchup from Cantonese to name a tiny selection.

Early Modern English

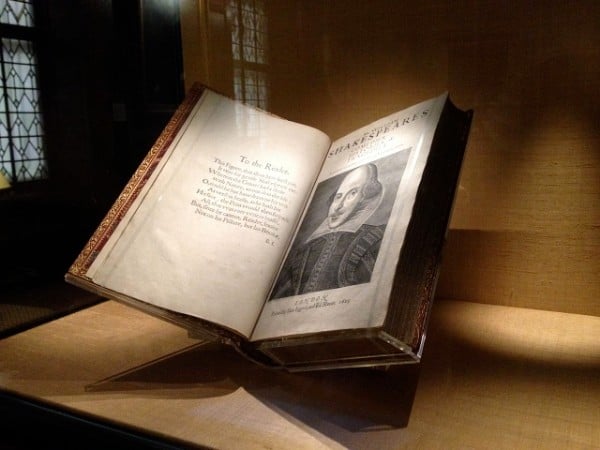

Shakespeare, writing in what we now call Early Modern English, inherited a rich and flexible language. When Shakespeare invented new words or played with syntax or engaged in puns and wordplay, he followed a long tradition stretching right back to the Anglo Saxon riddles or the Norse kennings.

The sponge-like nature of English and its benefits as a lingua-franca were not, and are not, without its darker side. During the days of British colonialism the use of English was often directly or indirectly forced on speakers of other languages. Jamaica Kincaid writes about this poignantly in her book A Small Place in which she explores Britain’s colonial legacy in Antigua:

‘But what I see is the millions people, of whom I am just one, made orphans: no motherland, no fatherland, no gods, no mounds of earth for holy ground […] and worst and most painful of all, no tongue.’

‘For isn’t it odd that the only language I have in which to speak of this crime in the language of the criminal who committed the crime?’

‘The language of the criminal can contain only the goodness of the criminal’s deed. The language of the criminal can explain and express the deed only from the criminal’s point of view.’ (Kincaid, 1988)

The future of English

English has also been identified as a prime suspect in language mass extinction. According to the Endangered Languages Project, ‘Over 40 percent of the world’s approximate 7,000 languages are at risk of disappearing’ (The Endangered Languages Project). People are abandoning minority languages in favour of major global languages like English, Mandarin and Spanish because of the social and economic advantages these languages confer.

Eminent linguist David Crystal, though, thinks the way forward isn’t as binary as has been suggested. Rather than English (and other language behemoths) wiping out all in their path, it seems that people are using language in much more subtle ways. New hybrid varieties of English are emerging around the world. Hinglish, for example, mixes Hindi and English and is mainly spoken by younger speakers. In these speaker communities, a speaker could well use one language formally at school or work (Hindi or English), and other varieties in other contexts (Hinglish with friends) and maybe a minority language at home with family. Crystal refers to this as bidialectalism or multidialectalism.

In England today we can see this in action with some speakers using a variety of English called Multi-Ethnic Youth Dialect. This fuses together different traditional dialects of English plus other varieties of English (for example Black English Vernacular or British Pakistani English) and sometimes other languages as well, for example Arabic or Somali. The history of the language journey can almost be mapped in the words of its living speakers.

It’s little wonder that, looking forward, linguists tend to speak of Englishes rather than English. I rather think Shakespeare would enjoy the innovation and adaptability of these new forms.

NEC offers a variety of English courses. Studying English Language and Literature at any level gives a great insight into English past and present and offers different and fascinating perspectives on language in use and action as well as building on key skills in understanding, writing, analysis and synthesis. The author of this blog, Maggie Pearson, has been part of the development and curation of six new English Skills workbooks for NEC’s Resources webstore. The first, ‘Key Skills in Orignal Writing‘ is designed to help you develop your own skills in this area and is available to download now.

For more information on our variety of English courses, incl: GCSE/A level English Language and Literature, explore our website or speak to our course advice team on 0800 389 2839.

Add a new comment

Current comments: 0